Reviewed by Nigel Price.

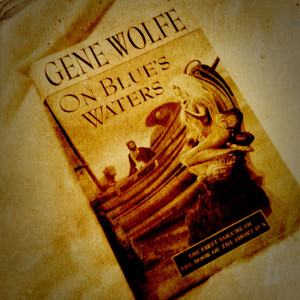

On Blue’s Waters is a fine book. Beautifully written, it is by turns thrilling and amusing, moving and intriguing but, like much of Wolfe’s work, it defies easy classification.

The most commonly used description for Wolfe’s series novels is “science fantasy”. This can be a slippery and misleading category. Some science fantasy is really fantasy with an added but superficial dose of science fiction props and scenery. Some science fantasy is only superficially fantastic, and uses the furnishings of fantasy to contain or perhaps conceal a science fiction rationale. Obviously, there is something of this in Wolfe’s writings, most famously in the seemingly mediaeval towers of the citadel of Nessus in The Book of the New Sun, which turn out to be disused spaceships. But, like many of Wolfe’s best books, On Blue’s Waters is both science fiction and fantasy, and while it shows that there is a rational, scientific explanation for much that appears fantastic, it also dares to suggest that there may yet be room in such a rational world for wonder, marvel and the inexplicable.

For this is a book where the parts are all in perfect harmony, and which works marvellously both as science fiction and as a haunting fantasy. Indeed, it is also in part a horror story, and a work of philosophical speculation. But above all, it succeeds as literature.

What were the great themes that first drew me to science fiction when I was a child and which have kept me enthralled ever since? Spaceships, aliens and the colonisation of other planets. Wolfe gives us spacecraft, his hero searching for the city of Pajarocu, where there is claimed to be a working shuttle capable of returning to the generation starship the Whorl. And when we finally get into space, the journey is as dangerous and exciting as anything for which we might have hoped. There are aliens too, terrific aliens: the fearsome inhumi, inhabitants of Blue’s sister planet Green. As their name suggests, and like all really good aliens, the inhumi are indeed inhuman, as remote and strange as you could wish. And yet, as Horn gradually and reluctantly comes to know his adopted son, the inhumu Krait, we learn as he does that even the monstrous inhumi have their needs and their reasons. As for the colonisation of other worlds, then that is the very subject matter of the book, as Horn as his fellow settlers seek to establish life on the planet Blue and build a new civilisation there.

But this is a fantasy too, one that gives us a quest, a mermaid of a sort, dreams, ancient gods, death and rebirth, and even beasts that talk (Oreb) and crew boats (Babbie).

It is a fantasy tinged with horror, however, for the inhumu are vampires of the most bloodthirsty and voracious kind. We will encounter live inhumations and hideous disinterments when the people of Gaon seek to kill predatory inhumi by burying them in the ground, only for the narrator to dig them up again as he seeks to recruit a secret army to combat the forces of Han which are threatening his city.

Horn’s encounter with the “devil fish” in the shallow tarn on the weed island in the middle of the ocean is horror fiction of a very high order, strongly reminiscent of the writings of Frances Hope Hodgson, an author Wolfe clearly admires. This whole section could have come from The Boats of the ‘Glen Carrig’.

As for philosophical speculation, On Blue’s Waters is seriously concerned with such issues as the cultural transfer of concepts, the qualities of the ideal ruler, the possible efficacy of prayer, and, even more fundamentally, the existence of God.

Taking up where The Book of the Long Sun ended off, On Blue’s Waters is the first volume of a new three part work entitled The Book of the Short Sun. The former book told the story of the saintly Patera Silk, and was written, as we learnt at the end, by his pupil, Horn. The new book is about Horn himself, though the narrator, the Rajan of Gaon, appears to be at one and the same time both Silk and Horn. How this came to be is not yet clear. (Wolfe’s list of “Proper Names in the Text” refuses to call the Rajan of Gaon “Horn”, but simply describes him as “the narrator”.) The book consists of two main narrative threads. The first is the narrator’s account of how, many years previously, Horn left his home and family and set off to find and return with Silk, who remained on the vast, decaying starship the Whorl after Horn and his fellows left to set up colonies on the planet Blue. The second thread recounts the narrator’s own adventures as the ruler of the city of Gaon. The threads alternate, and neither unwinds in entirely chronological order.

For all his exquisite prose and expertise at world building and characterisation, Wolfe’s special gift is in the engraving of subtle mysteries into the texture of his narratives. Tales of adventure, excellent in themselves, are detailed, deepened, and sometimes even undercut, by several further layers of meaning and significance. The hero, who in many of Wolfe’s best works is also the narrator, may not himself apprehend all these hidden meanings. But an alert reader will see the clues, and in careful reading and rereading may catch glimpses of previously unsuspected depths, where truths and ironies glitter in complex profusion.

But, heresy though it may seem to some, Wolfe also has his shortcomings as an author. Most notably, he seems at times to struggle with the pace of his narratives. For example, while Nightside the Long Sun is gripping throughout, the later volumes of the otherwise excellent The Book of the Long Sun are all considerably slowed by long and not always entirely riveting accounts of journeys through the multitude of tunnels which permeate the hull of the Whorl. And then the second half of the last volume, Exodus from the Long Sun, suffers from the opposite problem. The scope of the story rapidly widens and the pace suddenly quickens, as if the author realised that he had too much to say and not enough time or space in which to say it. The ending is deeply moving, but still seems rushed, which is disappointing after such a detailed and intimate unfolding of the story up to that point.

There are no such problems with On Blue’s Waters. The mysteries are present in abundance, tantalisingly disclosing a dozen truths while concealing a hundred more, but the pace of the story is judged to perfection. The narrator is reflective and discursive, but his musings are intertwined with the twin narratives of Horn’s past and the narrator’s present, both of which are packed with so much incident and significance that the reader is swept along by the action. It is an extraordinarily accomplished performance, and one which has its own organic momentum, building to twin climaxes as both the timelines reach their respective crises in the final chapters of the book.

To digress onto this matter of structure and the pacing of the narrative: it has been observed before that Wolfe is at his best with either short fiction up to novelette or novella length, or very long, multi-volume novels.

Though not immediately germane to this review, it is perhaps relevant to note that The Fifth Head of Cerberus, probably Wolfe’s most successful single volume work, is in fact made up of three linked novellas. Wolfe gives a fascinating commentary on this type of literary construction in his essay “The Living Earth”, in which he discusses Jack Vance’s The Dying Earth, another novel made out of linked novellas.

Most centrally, how can the shorter forms (of story) be used as stepping-stones to the novel? One way, as we have seen, is through continuing characters… (who appear in several different stories within a collection). ‘Short’ stories can be made longer…by adding incident, so as to approach the length of a short novel incrementally – it may seem too simplistic to work, but it does – by, above all, laying story after story at the same time and in the same place. Did Vance…realise that the Dying Earth itself was to be his greatest character? (Jack Vance: Critical Appreciations and a Bibliography, edited by Arthur Cunningham, British Library, 2000, p.96)

Wolfe’s long works are generally episodic in nature and, occasional problems of pacing aside, he has already shown that he can develop this form “by adding incident” quite brilliantly. Guided by, amongst other things, the Dickensian model of fictional autobiography, he sustains the reader’s interest in The Book of the New Sun throughout its entire length, skilfully moving his hero down the years and across the landscape, withdrawing characters from the narrative when they have become familiar and re-introducing them in settings that are fresh and unexpected, and even leaving himself room to include embedded, self-contained stories, the folklore tales of his far distant future, based though they often are on the distorted images of an unremembered past.

But in On Blue’s Waters, Wolfe adopts a far more complicated literary model. The narrator begins his story while he is himself only half way through his adventures. Far from home, a prisoner king in a foreign land, he still has much to do to survive, to bring justice and good governance to his people, to defeat their enemies, and to escape and, maybe, find his way back to his long lost home and family. Not only do his accounts of his recent exploits interrupt his attempt to tell the first part of the story, that concerning Horn’s departure from Lizard island and his long journey to Pajarocu, but his musings and comments on what he has written form yet a third strand to the novel. These comments include recollections of parts of the story not yet told, but which will presumably be recounted in the remaining two volumes, In Green’s Jungles and Return to the Whorl. The tone of the commentary, occasionally angry, is primarily wistful and nostalgic, and lends an extraordinarily elegiac air to the whole book. Most of all, the narrator, or that part of him which is still Horn, longs for the two women whom he has abandoned: his wife and childhood sweetheart Nettle, and the beautiful one-armed siren Seawrack.

Seawrack sings in my ears still, as she used to sing to me alone in the evenings on our sloop. Sometimes – often – I imagine that I am actually hearing her, her song and the lapping of the little waves. I would think that a memory so often repeated would lose its poignancy, but it is sharper at each return. When I first came here, I used to fall asleep listening to her; now her song keeps me from sleeping, calling to me.

Calling.

Seawrack, whom I abandoned exactly as I abandoned poor Babbie.

Seawrack

(On Blue’s Waters, chapter 6, “Seawrack”, p170)

Perhaps it is the cool detachment of the authorial voice he employs in many of his books, but while much has been written in praise of Wolfe’s ingenuity, relatively little has been said about his ability to depict and evoke emotion, which he can and does do extraordinarily well. I found many passages in On Blue’s Waters deeply moving.

The interruptive narrator is a literary device which goes back at least as far as Tristram Shandy. Wolfe’s use of it, if not entirely novel, is nevertheless both extremely skilful and highly effective. As we have seen, it allows him to maintain the pace of his story and to exercise a fine degree of control over its tone. We might also note that it even allows him room for the occasional embedded folktale, as in the legend of the pajarocu bird which Captain Wijzer recounts in chapter four.

But in that the narrator claims to have already died, and in that his identity seems to be in some way an amalgam of two different people, the very telling of the story casts a fascinating shadow of mystery and uncertainty over the whole of the book. What separates the two narrative threads is clearly more than simply the passage of time. One person seems to have become another. A narrative which appears at first to be a mechanism for conveying explanation becomes instead a source of paradox.

The structural harmony of On Blue’s Waters turns out to be the embodiment of mystery.

A last note on, and a final paradox from, the narrative structure of On Blue’s Waters: for all that the construction is intensely and successfully novelistic, and to that extent modern, it is also fundamentally classical and, specifically, epic in its design.

To backtrack, and enter a personal note to this review: the first book I ever read by Wolfe was The Shadow of the Torturer. I was completely bowled over by it, and, knowing nothing of the author, developed a number of theories about what sort of person might have written such a work.

I was immediately struck by the echoes of Great Expectations. This author could not only pastiche Dickens, he seemed to be able to write almost as well as him!

But the apparent familiarity with the Byzantine empire and the vague but constant evocations of late classical antiquity suggested to me that the author might be a classicist or historian of some sort, an impression that was reinforced by the cool clarity of the book’s tone. It reminded me of the better sort of English translation from golden age Latin.

I was suitably astonished, therefore, when I discovered that the author was in fact a process engineer by training, and the former editor of a technical journal in that field!

Now alerted to the reality of the situation, my further reading uncovered a rich seam of material in Wolfe’s fiction which clearly demonstrated a familiarity with and an interest in the details of that very discipline, process engineering. There is a haunted orange juice factory in Peace, and we get to learn quite a lot about how it works. There is a factory for making the robotic tanks known as talluses on the Whorl, and the reader of The Book of the Long Sun gets taken for a guided tour. The hero of On Blue’s Waters is a papermaker by trade, and Wolfe shows considerable interest in the details of both the papermaking process and Blue’s nascent bookbinding and publishing industry. We hear how Horn and Nettle chose Lizard island for their home because of the availability of water-power to work their paper mill and the existence of a good natural harbour into which they could float logs from the mainland. The narrator even tells us how he experimented to make ink, and speculates on the possibility of producing coloured inks.

(And is there a little autobiographical wordplay to be found in the fact that Horn and Nettle the book producers make their home on the Tor on Lizard, given that “Tor” is also the name of Wolfe’s publisher?)

All this wonderful, practical detail lends great solidity to Wolfe’s imagined worlds, but Wolfe, engineer though he is to his fingertips, really is also a fine classicist, even if not of the professional variety that I first imagined. In addition to the deeply impressive Soldier books, which are actually set in ancient Greece, there are classical references and influences throughout Wolfe’s fiction, from the titular hell-hound who presides over The Fifth Head of Cerberus to the legendarily curious female who lends her name to Pandora by Holly Hollander.

Others have already pointed to the influence of the Odyssey on On Blue’s Waters. Horn does indeed wander over the sea like Odysseus and longs to return, after his journeys, to the wife he left behind. His son Sinew is like Telemachus to the extent that he does set off in search of his missing father. Like Odysseus, Horn encounters a siren, though he disastrously fails to make sure he is tied to the mast when she starts to sing.

Such divergences from the template are significant, because this is no slavish retelling of ancient story, but rather the classically influenced forging of an altogether new and modern myth. Wolfe follows Virgil’s precedent and feels free to dismantle and re-assemble the components of Homeric epic in order to create a truly modern version of the genre. Odysseus’ crew were turned into swine by Circe, but Horn’s most faithful crew member Babbie actually is a pig, or at least a hus, which is an awfully pig-like creature, for all its unaccountable multiplicity of limbs! (Later, we gather, Horn will meet and befriend a mercenary on the Whorl whose name is simply “Pig”.)

So it is presumably no casual accident that the narrative form of On Blue’s Waters is one which allows Wolfe to start his story “in medias res”, as Horace advised in the Ars Poetica. We do indeed start in the middle and go back to the beginning, and there are prophecies and forward references to indicate what is still to come.

It is traditional for an epic hero to seek prophetic guidance for his mission and, like Aeneas, Horn visits a sibyl. Maytera Marble, the “chem” or android sibyl we first met in The Book of the Long Sun, is herself an augur now, and searches a fish’s entrails in an effort to discern Horn’s fate.

The episode is perhaps more like Perseus’ visit to the Graeae than Aeneas’ visit to the sibyl. Maytera Marble is now blind, her electronic eyes having finally worn out. The graeae had only one tooth and one eye in common, which they shared between them. Maytera Marble has already fitted herself with the dead Maytera Rose’s processor, so that they to some extent now share memories and personalities. She failed to take Maytera Rose’s eyes, however. In another evocative inversion of the myth, instead of taking the Graeae’s eye in order to get them to prophesy, Horn accepts one of Maytera Marble’s robotic eyes from her, along with a commission to find a replacement for it if he can, should he ever succeed in returning to the Whorl.

Like the Aeneid, On Blue’s Waters is concerned with the migration of a people following war and destruction, and like Aeneas, Horn is committed to bringing his family’s gods from his old home to his new. As Aeneas meets Tiberinus, so he is also to encounter on Shadelow the tutelary deities of this new world of Blue, the mysterious Neighbours, Blue’s original inhabitants. Critically, he must and does achieve rapprochement with them, thereby smoothing the way for his fellow settlers.

As we have seen, structurally, On Blue’s Waters is a fundamentally mysterious book. But the story not only contains mysteries, it really is all about secrets. Horn is seeking the city of Pajarocu, a settlement whose location is deliberately kept secret by its inhabitants. He is going there in the hope of finding passage on a shuttle back to the Whorl, so that he can look for Silk. But when Horn consults Mucor as to Silk’s whereabouts, she reveals that Silk has asked her not to reveal his location. This, then, is a book in which the hero seeks a hidden man by way of a hidden city.

But while many questions remain unanswered (Is Blue Urth, or, at least, Ushas, and Green Lune? If Blue is Urth, is the tall Neighbour Horn meets the persisting spirit of the lofty Severian? Is the Land of Fires Tierra del Fuego? Is Pajarocu located on the site of Nessus? What does a leatherskin look like, with its three jaws? What is the secret of the inhumi that the dying Krait confided to Horn? And why do elephants in Gaon have more than one trunk?), Horn does eventually find the hidden city of Pajarocu, and there may yet be enough information in the book to answer, at least in part, the central riddle of the narrator’s identity.

We learn eventually in chapter fourteen (“Pajarocu!”) that Pajarocu is a sort of Platonic city, a schematic replica or shadow of the layout of the real Pajarocu on the Whorl. What its inhabitants have done “is to duplicate its plan to perfection – without duplicating, or attempting to duplicate, its substance at all.” (p348)

This doctrine of “ideas”, which ultimately derives from Plato and is most famously illustrated by the parable of the cave in his work The Republic, is announced by Wolfe as early as the opening of chapter two, where the narrator is describing some people’s “talent” of being able to do nothing.

Silk said once that we are like a man who can see only shadows, and thinks the shadow of an ox the ox and a man’s shadow the man. These people reverse that. They see the man, but see him as a shadow cast by the leaves of a bough stirred by the wind. Or at least they see him like that unless he shouts at them or strikes them. (p49)

Silk refers to the traditional Platonic notion that the phenomenal world is a sign and consequence of a higher reality which humans in their ignorrance can only dimly perceive. The narrator, however, inverts this concept and says that lazy people actually do perceive reality but are too indolent to realise it, thinking it merely a sign or a seeming unless “reality” in some way gets up and slaps them in the face and thereby draws their attention to itself. Somewhere behind the scenes, Wolfe seems to be suggesting the possibility that the reader has actually been shown all the answers to his or her questions, but has failed to appreciate the fact, mistaking answers for hints or clues. Duly chastened, this reviewer has to confess to his lack of perception, mesmerised as he is by the beauty of the play of shadows that flit so gorgeously across the surface of this text.

The people of New Viron recognise the need for a ruler to lead their town, and commission Horn to travel to the Whorl to find Patera Silk, the Calde of old Viron, so that he can become the Calde of New Viron too. Although we do not know the full circumstances, it is clear that Hari Mau and some other men from Gaon have also returned to the Whorl in search of Silk, so that they can install him as their Rajan. Mistaking Horn for Silk, they kidnap him, and return to Blue and make him their prince. But the real irony is not so much that Horn’s mission is frustrated by those carrying out an apparently identical mission on behalf of another settlement, so much as the fact that Horn has indeed become like Silk, and may even be Silk in some way which has not yet been fully explained.

It may be that the combination of his trials and adventures, combined with his abiding memory of Silk and strong desire to imitate him, have turned Horn into someone very like Silk. They have certainly turned him into a fine and honest ruler. The frame story of the narrator’s adventures as Rajan of Gaon leave us in no doubt that, while far from perfect, Horn-Silk is in fact a very good prince. He is honest and upholds the law in court without favour or prejudice, always doing his best to establish the facts of the cases brought before him. He works to strengthen the economy of Gaon, while at the same time creating work for the unemployed by engaging their labour to build the diversion of the river Nadi which will bypass the Lesser Cataracts downstream of Gaon, thereby opening access to the sea and greatly increasing trade on the river. We see Horn-Silk as an inspired leader during time of war, heartening his troops and devising clever stratagems by which to defeat a numerically superior enemy. Lastly, he is a ruler who is happy to abdicate his responsibilities once a suitable successor has arisen. He does not crave power for its own sake, but, on the contrary, yearns only to return to his wife Nettle and his old life at the paper mill on the island of Lizard.

Clearly, Horn, who has always striven to follow the example of his saintly friend and former school master, has in some measure succeeded. The exact means by which Silk and Horn have merged remains a mystery, but it is appropriate that, finally, their personalities should have achieved a measure of harmony

Zenslinger

Am I the first to say how beautifully written this is? Great work.

Nigel

Thank you. It was written a few years ago now, and before In Green’s Jungles was published. It would be good to go back and review the whole Short Sun sequence.

Nigel

Slojo Coma

I agree – this was really well written.

I just completed the series and would love to read a full review!

Good work, Nigel.